Mitchell Joachim is the Co-founder of Terreform ONE, a nonprofit organization focused on philanthropic architecture and urban, ecological design. He’s an Associate Professor of Practice at NYU, a TED Senior Fellow, and was chosen byWired for “The Smart List” and by Rolling Stone for “The 100 People Who Are Changing America.” He co-authored the books “Super Cells: Building with Biology” and “Global Design: Elsewhere Envisioned.” His design work has been exhibited at MoMA and the Venice Biennale. Formerly, he was an architect at the offices of Frank Gehry and I.M. Pei.The views expressed are the author’s own, and do not necessarily represent the views of Qualcomm.

Cities have always had clear identities, a collective understanding of their value and purpose. We see this idea strung through the history of cities—first as military or religious hubs, then as industrial centers, and now as centers of commerce and capitalism. Today, we’re at the beginning of the next great global urban shift, which could take decades, even a century, to complete. The emergence of connected smart city technologies is putting us on the path to the optimized metropolises of the future.

Urban reinvention is not as extreme an idea as it may sound. I’m not suggesting we level downtown Chicago or scrap SoMa, but rather that the way we feed resources—food, water, power, connectivity—into our population centers will one day need a reboot. Our current systems, be they pipes or tubes or buses or semis, eventually won’t be able to support explosive urban growth.

Right now, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities. By 2050, U.N. estimates put that number at closer to two-thirds. This uneven growth, met with the limitations of our current systems, is one of society’s greatest challenges going forward. It continually spurs a generation of urban engineers (“urbaneers”) to challenge how we currently think about the future of our expanding metropolises.

Retired ships are repurposed to create buffer zones to better manage floods and surges. (Image Courtesy Terreform ONE.)

To understand where our visions for urban design come from, you first need to understand how I think about design. To me, a designer is also an inventor. We look at context and at the ecosystem, and think about how we can change an idea or product for the better. I’m talking about hacking the system, about improving an object’s relationship with the people who will interact with it.

For cities, specifically, that means a couple things.

First, respect what we have. We have experienced thousands of years of human culture and history, of grand heritage that makes up these places. Whether you’re in New York or somewhere in the Middle East, you can’t just toss this legacy away.The Jetsons’ world of glass houses in the clouds isn’t what’s going to happen.

Second, we need to think about interaction: how, when, why, and where an individual or group will come face-to-face with our designs. There are many disciplines to consider, many levels of scale; there are evolving narratives. A smart city would be an integrated model that happens over time and accepts and adapts all the different technologies along the way.

For the time being, that means making subtle updates to the facilities and fixtures that already exist. Projects that convert derelict phone booths into Wi-Fi hotspots, turn trash cans into composters, create mesh networks out of public transit buses, and use street lights to map parking spaces are springing up more and more. There’s also technology embedded deep into infrastructure to monitor the flow of resources, such as water and gas, and spot potential issues and deficiencies.

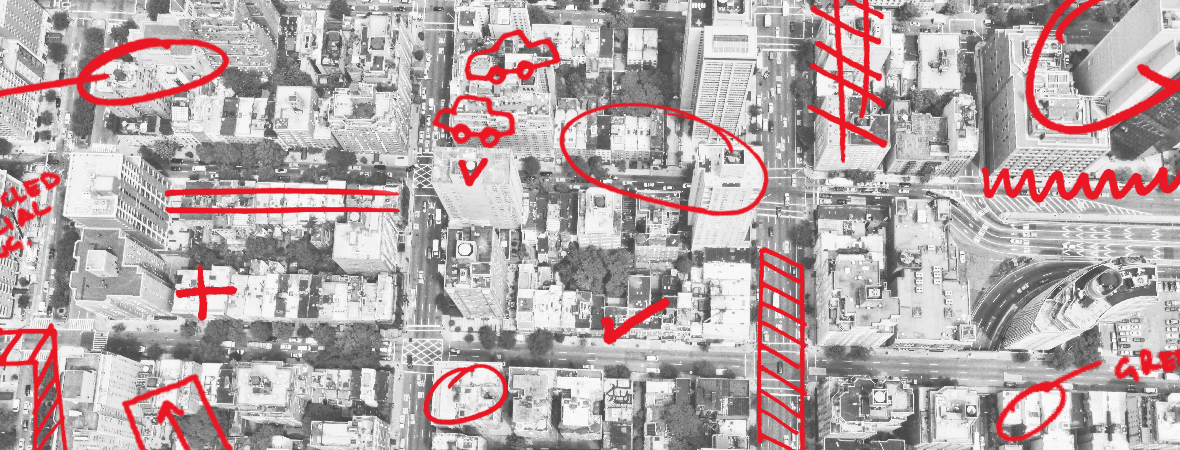

All this helps improve day-to-day life in the short term—perhaps you’ll get to work a little more quickly or worry less about losing water pressure in the shower—but is only the beginning of what smart cities will need to become to support urban growth. What happens when what we have starts to decay and break down? This is where we start considering sweeping changes. What if my car was stackable? What if it’s part of a swarming, shared-ownership car system?

Right now, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities. By 2050, U.N. estimates put that number at closer to two-thirds. This uneven growth, met with the limitations of our current systems, is one of society’s greatest challenges going forward. It continually spurs a generation of urban engineers (“urbaneers”) to challenge how we currently think about the future of our expanding metropolises.

To understand where our visions for urban design come from, you first need to understand how I think about design. To me, a designer is also an inventor. We look at context and at the ecosystem, and think about how we can change an idea or product for the better. I’m talking about hacking the system, about improving an object’s relationship with the people who will interact with it.

For cities, specifically, that means a couple things.

First, respect what we have. We have experienced thousands of years of human culture and history, of grand heritage that makes up these places. Whether you’re in New York or somewhere in the Middle East, you can’t just toss this legacy away.The Jetsons’ world of glass houses in the clouds isn’t what’s going to happen.

Second, we need to think about interaction: how, when, why, and where an individual or group will come face-to-face with our designs. There are many disciplines to consider, many levels of scale; there are evolving narratives. A smart city would be an integrated model that happens over time and accepts and adapts all the different technologies along the way.

For the time being, that means making subtle updates to the facilities and fixtures that already exist. Projects that convert derelict phone booths into Wi-Fi hotspots, turn trash cans into composters, create mesh networks out of public transit buses, and use street lights to map parking spaces are springing up more and more. There’s also technology embedded deep into infrastructure to monitor the flow of resources, such as water and gas, and spot potential issues and deficiencies.